States Want Pot to Grow Greener as Legal Cannabis Expands

As more states legalize recreational and medical marijuana, they’re confronting the reality that cannabis production involves using huge amounts of pesticides, energy, and water, while generating tons of plant and packaging waste.

The result is a patchwork of air, water, pesticide, and waste regulations for the industry across dozens of states, even as the substance remains illegal at the federal level.

States like Michigan, where the Marijuana Regulatory Agency will begin accepting business licenses in November, have adopted rules on issues like industrial wastewater, water resources, and land management for cannabis growers. Illinois, which legalized recreational marijuana this year, will factor environmental planning—including conservation and efficiency efforts—into its scoring of cultivation center applications.

Colorado is tweaking some elements of its marijuana environmental and sustainability regulations after becoming the first state to allow recreational marijuana use in 2014.

And New Mexico, where decriminalization took effect July 1, just launched a committee to work through environmental and other aspects of the legalization of recreational pot in advance of the state’s next legislative session. New Mexico’s focus on climate change and water issues will likely figure into the proposal that emerges, said James Kenney, secretary of the state’s Environment Department.

“We would want to make it the least footprint for producing as possible,” Kenney said.

Among other industry aspects, the department would regulate the safety of commercially-produced food with THC—the psychoactive compound that gives marijuana users a high.

Waste, Water Use Weighed

Expanding or establishing a marijuana industry raises resource questions for states: What land will be used for production? Where will water to grow the crop come from? What to do with the waste?

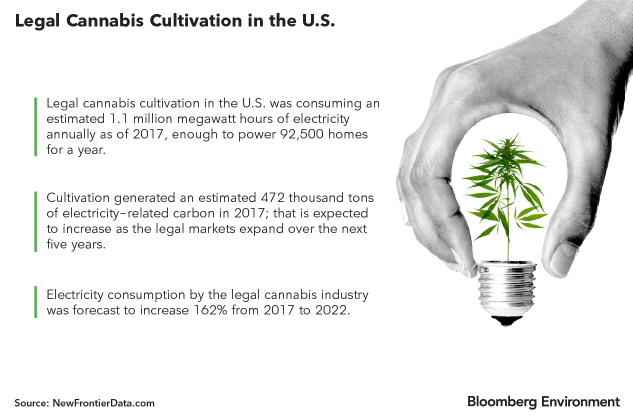

Pollutants include pesticides, fertilizers, and solvents, while indoor marijuana production can be energy intensive. Legal cannabis cultivation uses enough electricity annually to serve 92,500 homes for a year—a figure that’s expected to grow, according to cannabis industry analytics firm New Frontier Data.

Analysts have also attempted to measure the cumulative environmental impacts of illegal and state-licensed cannabis cultivation.

Total 2017 combined energy consumption in legal and illicit growing was estimated at 4.1 million megawatt hours, roughly equal to the electricity generated by the Hoover Dam, according to New Frontier Data’s October 2018 report.

Data Tracking

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment is developing a tracking system for environmental data, including waste produced from the industry, and water and energy used.

In Denver, electricity use from cultivating cannabis and manufacturing infused products jumped an average of 36 percent per year from 2012 to 2016, according to a 2018 Denver Department of Public Health and Environment report.

The legislature approved a measure last year to relax a rule requiring cultivators to blend cannabis plant waste 50-50 with non-marijuana waste. The original aim was to prevent people from being able to recover and reuse marijuana, but it resulted in a “doubling of waste going to landfills,” said Kaitlin Urso, an environmental consultant for the state department.

The department is also studying the cannabis industry’s impact on air quality, with results expected in March 2020. The extraction process produces volatile organic compounds that form ground-level ozone when they react with sunlight, creating negative health effects.

EPA Silent on Pesticides

In California, cannabis represents a tiny percentage of land and water use, but has a possible impact on small streams, among other issues, said Van Butsic, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-director of the university’s Cannabis Research Center. California’s push to legalize cannabis was in part driven by the need to bringing illegal growers into the regulated market to address water and chemical use.

Cannabis plants each need about 6 gallons of water a day, according to a 2018 report from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Habitat Conservation Planning Branch. That means California growers may divert springs and streams for irrigation, disrupting wildlife, the report said.

Berkeley researchers at the center are now looking at cases where people aren’t entering the legal market.

“We’d like to know if there are barriers that can be removed,” Butsic said.

Marijuana’s prohibition under federal law also affects how states try to build a regulated industry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency hasn’t evaluated pesticide use related to the crop.

States like Nevada are left to come up with lists of pesticides that aren’t prohibited based on risks to human and environmental health. The Nevada Department of Agriculture hasn’t endorsed or recommended any of them, spokeswoman Rebecca Allured said in an email.

Georgia barred the use of pesticides unless certified organic by a handful of licensed growers, under a law enacted this year that allows production and sale of cannabis oil with low levels of THC. California is creating a program that will enforce organic cannabis standards starting in 2021.

Pesticides allowed in Washington are “pretty much natural pest deterrents,” Stephanie Davidsmeyer, communications consultant for the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, said in an email. Rules under development will outline mandatory pesticide and heavy metals testing and should be final by late 2020, she said.

Plastic Packaging Criticized

Washington is also revising its marijuana product packaging and labeling requirements, she said. Critics of various state regulations say some of the mechanisms intended to protect the public result in overpackaging that is mostly single-use and plastic.

“They didn’t take environmental health into consideration,” said James Eichner, co-founder of California cannabis packaging company Sana Packaging that uses materials including hemp and reclaimed ocean plastic.

The company is targeting the most sustainable options for major cannabis packaging types and sees a “sustainability ethos within the industry,” Eichner said. It’s also time to reconsider some regulations, such whether a non-activated cannabis flower needs to be sold in thick, child-resistant containers, he said.

Compliance with regulations is the top concern, said Michael Markarian, CEO of Contempo Specialty Packaging, a Rhode Island company that produces cannabis packaging. He said labeling requirements can force one gram to be placed in an enormous container.

Contempo is looking to develop packaging that has fewer environmental impacts, and determine what customers are willing to pay for it, Markarian said.

Industry Efforts

The National Cannabis Industry Association is working on a white paper with guidelines for best management practices relating to environmental stewardship and sustainability, with the goal of releasing it later this year, spokesman Morgan Fox said.

“The industry continues to explore ways it can become even more sustainable and environmentally friendly,” he said.

The national Cannabis Sustainability Symposium, put on by the Cannabis Certification Council, will convene experts from across the country to focus on the industry’s environmental issues. The next symposium will be held Oct. 4 in Denver, with future events planned for Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco, and Portland, Ore. The council seeks to serve as a standard-holding body for the industry.

Cannabis producers have shown a strong commitment to stewardship and sustainability, said Urso, the Colorado environmental consultant, who previously worked with craft brewers, oil and gas producers, and sand and gravel mining companies.

“I’ve been extremely impressed by the marijuana industry,” she said. “I’ve never seen a higher adoption rate around best management practices. They’ve shown such a willingness to do the right thing.”

—With assistance from Paul Shukovsky, Keshia Clukey, Alex Ebert, Stephen Joyce, Jennifer Kay, Laura Mahoney, Chris Marr, Andrew M. Ballard, and Emily C. Dooley.